Programming Each Other

September 24, 2010

The Public School was started by Sean Dockray, currently director of Telic Arts Exchange, and a group of collaborators in 2007 in Los Angeles. With the help of Caleb Waldorf, The Public School Berlin was launched in late September 2010.

Caleb Waldorf: My involvement in the project came shortly after attending the second class held at the school in LA titled, Ranciere: The Politics of Aesthetics (and/as an Ethics). I found the class to be amazing and at the completion of the course emailed Sean to ask if the school needed any help, with well, anything. I was super excited and wanted to do whatever I could to contribute. I then joined the D.A.N. a few months later on the first “rotation” of the committee.

To hopefully paraphrase Sean accurately, one of the motivations for starting the school was to engage with the question of how labor unfolds in the programming of an arts space. Telic Arts Exchange was organizing exhibitions and preparing projects, which while diverse in terms of form and duration, still largely took place within the context of an exhibition format. Orchestrating this type of programming requires a significant amount of labor by the organizers “behind the scenes,” and yet the actual experience of the production could be very short. What The Public School then did was try to reorient that structure toward another one: a school. After all, a school is also one system of programming, just like an exhibition is.

Legwork: It is indeed. So I suppose just as an exhibition has a curator, a school has a programmer or a principal. I find it interesting that The Public School emerged in an art space context. After the curatorial turn, this context enables us to see, discuss, and thematize that “behind the scenes” figure, be it a curator, a programmer, or a project author.

CW: There is a long history of artist-run educational projects, and it seems like more and more are popping up every day. Over the last year and a half we have been taken up into many conversations about art and education that are happening in the arts/academic worlds. We participate in these both directly and also by being mobilized within a specific conversation as an “example.”

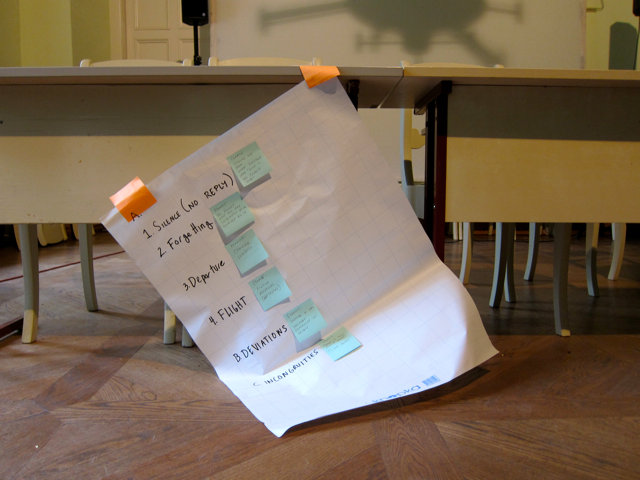

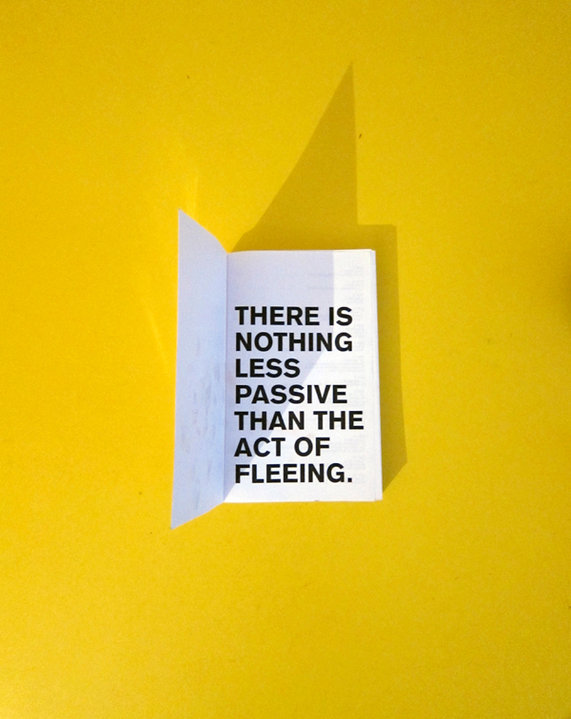

Part of our motivation for organizing There is nothing less passive than the act of fleeing… this summer in Berlin was to think about our project in relationship to these broader conversations that have taken and are taking place right now – but not only within an arts context. In other words, we wanted to have a conversation to help us consider issues that aren’t always covered in an art space context. That being said, the texts discussed in Berlin don’t deviate too much from some of the conversations that have been taking place in Los Angeles for the last few years. In fact, I don’t see how we could have created the program without the classes and people who have participated there.

LW: So what are the specifics of the facilitating function/act here? It sounds like there is more than a random exchange of experience.

CW: I’m not entirely sure it is random. For me it is very much an organizational project that tries to figure out a discursive space that resist traditional formations of knowledge, both in its accumulation and circulation. To be even simpler: how do we learn things, organize people, work with people, practice knowledge?

LW: It looks like your strategies to deal with these issues and to answer these questions are in a way pre-determined by the contextual space of origin of the project. What I mean is that maybe being placed within an art context is exactly what creates conditions and possibility, a way of thinking, of playing with detaching, the overcoming of what you call “discursive spaces.” To play with them, to make them a bit more open than academia usually does. Or an art institution usually does.

CW: I think so, but it is a very difficult to identify the “art” in the project. Ultimately I think even addressing that brings up another issue, which is whether we want to hold on to “art,” to that term. Do we have any investment in “art?” Is there a strong desire to challenge contemporary notions of art practice via The Public School so we could say that there is a different way of working as a contemporary artist? Or do we want not to have that conversation at all and say that this is not art but something completely different? I don’t have a very well formulated idea on any of these questions, but I still hold onto the term art at the moment. In my practice, both within The Public School and with other projects, this is something that I am trying to figure out. And my position is one that ends up being somewhat schizophrenic, and I move back and forth to different sides of the argument(s) often.

All that being said, a large portion of people involved in the project are not artists. The Public School Los Angeles committee is comprised of an architect, a couple of artists, someone who studies comparative literature, etc. In New York, there are people more involved in publishing and architecture. In Helsinki, they have architects, artists, musicians. It is quite a good mix, all of whom aren’t familiar with contemporary (or historical for that matter) art practices, and who I don’t think have an investment in the project as “art” per se.

Just as a quick anecdote from the Berlin seminar—the person with the best attendance who only missed one of the thirteen days is doing his Ph.D. in political philosophy here in Germany. I know from separate conversations outside of the seminar that he has very little knowledge of contemporary art or these kinds of artist projects. He came because he was at first curious, and he stayed because he enjoyed the conversations and the framework that supported them. Now given that this seminar was very much text oriented (many of our classes are not), he seemed particularly attuned to how the conversations unfolded and how everyone involved interacted, which he said he felt was very different from what he is used to. This is a common reaction for those participating.

What I think struck this person is something that is often the case, which is that the person facilitating a class is not the most knowledgeable on the subject being “taught.” More often than not there are others in the room that may have more “expertise” if you could call it that. So within the context of a class there is a lot of adjusting and readjusting that happens to find a common ground to talk and think together. Sometimes this doesn’t happen, and you can have a really strange class! But more often than not it can be extremely productive. Maybe when you are not sure where the conversation is centered, where your position is located, where the knowledge is concentrated, these aspects allow for some divergent things to take place.

LW: But that is interesting. It still has an art element to it, but displaced. It still contains both things but is not explicitly either of them. The example of the schizophrenic body, neither/nor; it’s both but not through an explicit manifestation. It comes exactly through having both theory and practice classes.

CW: Yes, and we think about that while programming the school. We try to have theory classes that lean towards practice, and practice classes that lean towards theory. It doesn’t need to be a text, but there should be some level of criticality involved.

For example, someone proposed a class called Making Furniture. My friend Isaac Resnikoff, who is an artist and wood worker, agreed to do it. So we thought it would be great if the pieces of furniture we built would teach different furniture building techniques – different kinds of joints, specific cuts, and using all of the tools in his shop. So he designed two pieces of furniture that were pedagogical. That has nothing to do with reading theory, but it is a way of thinking about a practice where you’re learning through making.

Also, another good example comes from one of the first class proposals at The Public School Los Angeles, which was called Sadism and Masochism. The class description (what would take place) was “Theory and Practice.” It was one of the most popular classes, so we decided we should schedule it. I don’t have a lot of experience on this subject matter, but it is something I was interested in, so I decided to take it on. What ended up being organized was a class in which we read theory, fiction, we had a screening and a whipping demonstration by a woman who had been involved in the Los Angeles BDSM scene for over 30 years. In addition, we got invited to do something at a conference where we did an “arousal” performance that lead into a talk by Niklaus Lagier. It was a talk that involved him reading short excerpts from a text we read in the class interrupted by someone demonstrating flagellation. This one class turned into a web of different activities: historical, theoretical, public events and publishing. And all it took was the title, “Theory and Practice.” The broadest possible description. But once it got inserted into The Public School, there is somehow a potential there for all of these insane things to happen.

LW: I guess that is what I could call the reversed process of knowledge production and articulation: the final product is not anticipated in advance, there are no formal prerequisites of what it should be. Apparently this is exactly what enables the production of additional (new?) knowledge, as opposed to re-articulation of the one that has been there before. One might say it happens randomly. However what is interesting to me it is its logical flow: programming a space – questioning it and turning it into a durational programming of knowledge without an end point, basing such programming on participation without expectation, which in a way brings us back to the space, but not in the same terms of it being a frame. Could you maybe elaborate a bit on this?

CW: It has a lot to do with time and where energy is placed within this space of cultural production. Running a school plays around with these relationships – where people are spending time in the space (both physical and discursive) and what they are doing while they’re in this space.

The “production” of The Public School is happening in the instantiation of the class. People are talking on the website and figuring out what it should be. The committee is helping facilitate that process and then the class happens. It goes like this basically: People propose a class, people talk about the class, a class is scheduled, that class spins off into other classes. So the programming takes place among many different people who are communicating and relating in various forms.

LW: So The Public School could not be seen as a project of relational aesthetics?

CW: Well, we spent a lot of time thinking about relational aesthetics within the context of a few classes. I don’t find Bourriaud very convincing or the projects he supports to be incredibly exciting or that different from other forms of artistic production. But that is, of course, a huge oversimplification that we’ll have to skip going into detail with at the moment.

LW: Could it be considered as a critical approach to it?

CW: For me, probably, but not necessarily for other people. Because not everyone involved in the project knows or cares about what relational aesthetics is. And maybe they shouldn’t! It is a very specific thing to talk about, which might not relate to so many folks.

LW: What about collaborative aesthetics?

CW: What is that?

LW: I don’t know, we can just come up with that now.

CW: Yeah, well, maybe it is something that dialogical aesthetics relates to – relocating where art happens. In the given case, art happens in the space of a certain dialogue, collaborations between people.

The question of friendship is also interesting here. I’ve been trying to figure out, first what exactly friendship is, and then how it (although “it” isn’t the right word) operates as a basis for a certain kind of collaboration. This is still very much unworked in my mind, but I think it is important to focus on relationships that resist territorialization by current dominant systems, whether they be economic, cultural or political.

LW: But you realize that in a way The Public School is becoming an institution, even though it does sort of deconstruct more traditional ones and provide alternative solutions.

CW: Of course, without a doubt. But this issue is at the forefront of many conversations that we have, so there is certain self-awareness that is productive in defining the project. The other thing is that the project has no money, no support and no real plan for moving forward. There is nothing to hold on to at The Public School other than an indeterminate shared idea of what it is and the practice of that idea. And that is the difference: institutions generate techniques to maintain their own institutionality. They build technologies to generate themselves, to keep themselves going. The Public School at its core doesn’t build technologies to keep itself going, but to, perhaps, unwind itself. I haven’t really thought about it in any specific terms, but it doesn’t have the same motivation or ability to generate all these techniques to keep itself going as a static whole. And where is it centered? When one school closes down, does that change The Public School? The Public School is both instantiation in a specific city and something that is bigger than that. But what that bigger thing is, isn’t unified or concrete. What keeps it going are the people who are involved in it. There are around 30 – 40 people on the committees. There are 4,000 – 5,000 “students” (people who have set up accounts on the website). It is hard to institutionalize a diversity like that when anyone of those people in anyone of the cities can swoop in and participate at many different levels.

That being said, The Public School has relationships to institutions. For me it is interesting to work adjacent to and beside institutions, but not with the goal to take them over or replace them with another hegemonic force. Perhaps we are an alternative. Perhaps The Public School could destroy certain entrenched ideas, but that is extremely hard to predict. It seems more productive and important to continue to develop positive actions for people to escape or leave those things that they find stifling or limiting, whether creatively or politically. At this point, The Public School is not going to replace higher education. It isn’t a model that works with the idea of taking down dominant power systems as a whole. It works at a much smaller scale, which may be where change needs to take place.

LW: We are framing our current issue of Legwork around the idea of virtuosity. For me what is interesting within The Public School is that it (and maybe I should say in a virtuosic way) combines two moments of mastery and dilettantism. It is floating in between them.

CW: I don’t know if we are trying to master something. We are trying to learn something, but I am not sure if we know what it is. Or I am not sure if we learn it! It is a sort of accumulation. I feel like knowledge is gathered in the space and across the schools, but very rarely does it happen that there is a clear proposal to learn something and that people actually learn it because the space allows for things to become more abstract, to go another direction based on participation.

LW: But that’s what I am saying. I was trained as a philosopher, and now that I got out of academia and into the real world, I see that this is the only way mastery can happen. This Enlightenment ideal of knowledge gain that ‘real’ institutions are trying to provide is not possible. It is an oxymoron in a way. Therefore, for me, what I see happening in The Public School has more to do with mastery than in an academic institution.

CW: Okay, now I see what you meant. Yes, it is more operative than instrumentalized. The Public School does rely on people that have been studying philosophy and other disciplines within an academic or professional context. I think it is difficult to abandon these forms completely. And as I mentioned, you aren’t necessarily going to learn things in the same way as you would getting a Ph.D. It is not an infrastructure for that form of knowledge. This is not good or bad; it is simply a fact. What is exciting is to see how knowledge can work within a different pedagogical container like The Public School, and how it can seep outside of the institution.

But not an organizational logic that works from above. One of the things that we often face is that many people email us asking if they can use our website because they see it as a good tool. But for us The Public School is not a tool. It is all this other stuff I’ve been rambling on about.

It is an everyday practice and ongoing (and shifting) sets of relationships. There are no dominant expectations, no ideology and no grand plan. But there is a thickness and opacity that you feel once you get involved.

http://berlin.thepublicschool.org/

» Co-working

⊕

Comments Off on Programming Each Other